|

Contents:

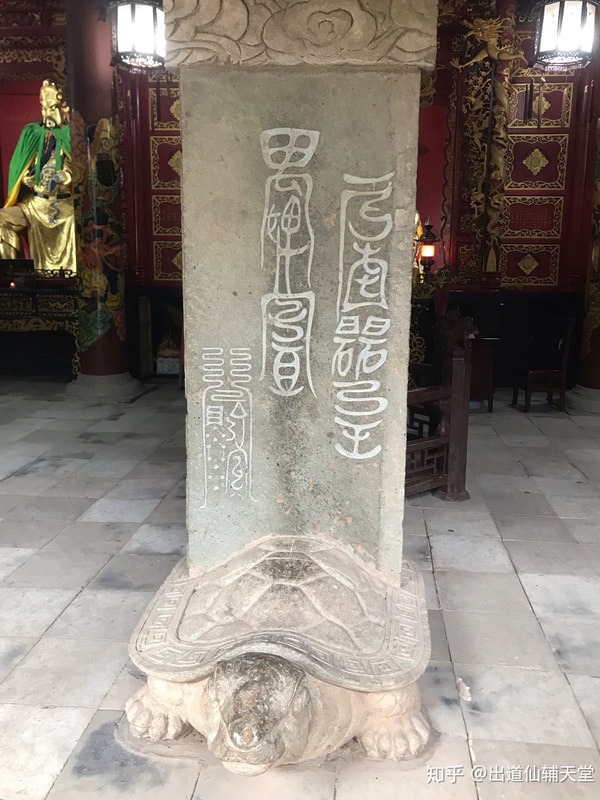

I. ForewordThis article is a continuation of the original “Parallels Between Sun Wukong and Wu Song” article by Jim R. McClanahan. Please see the epic original for the full introduction and analysis of the first 7 points here: Parallels Between Sun Wukong and Wu Song IntroductionThe two characters Sun Wukong from Journey to the West (1592) and Wu Song (武松) from Water Margin (c. 1400, shuihu zhuan, 水浒传) are among the most influential figures of Chinese literature. Moreover, the pair appear to share a striking number of similarities from their physical traits, achievements and background, as described in their respective novels. This article was written to identify these similarities and to break them down for deeper understanding. In total, Sun Wukong and Wu Song appear to have 13 distinct features that display their parallels. The list below records each parallel, as well as providing an analysis with examples to support each point. The first 7 points on this list are credited to Jim R. McClanahan; I am only including a very brief summary for each of them. Please visit the original blog page (see para. I) for the full article with well-researched detailed explanations. Para. 8 onwards are points of my own. 1. Reformed Supernatural SpiritsParallel 1: Both were originally demonic spirits, subdued by a religious figure and imprisoned under stone for centuries.

2. Tiger SlayersParallel 2: Both are known to have killed a tiger, a feat that displays the masculinity of a hero.

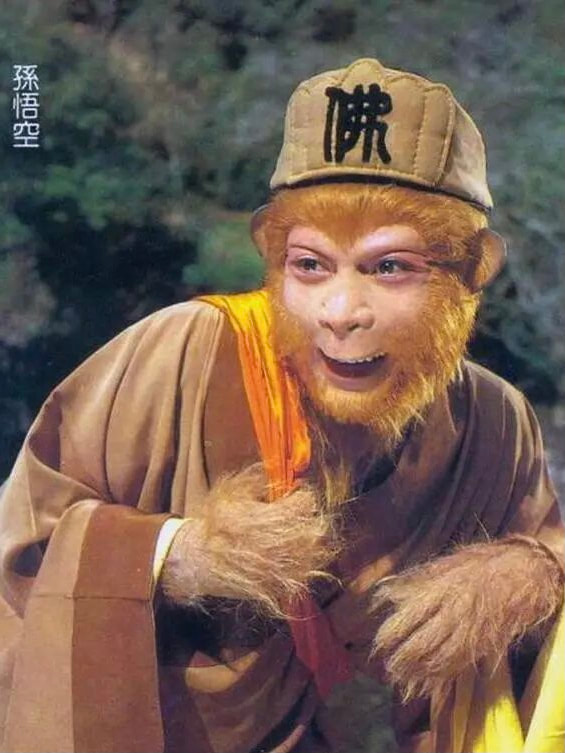

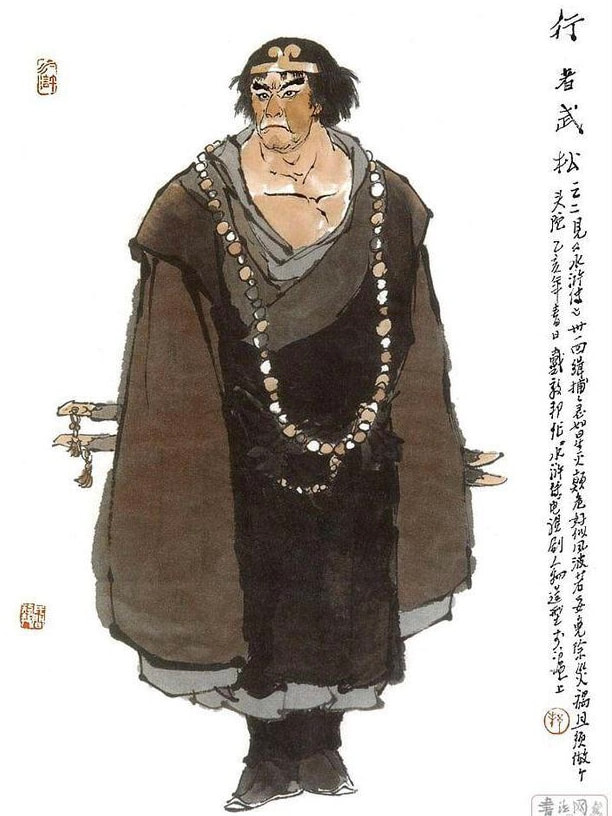

3. Buddhist Monks with Matching Religious NicknamesParallel 3: Both have converted to the law of Buddhism and assumed the byname “Pilgrim (xingzhe, 行者)”.

4. Monastic Martial ArtsParallel 4: Both are depicted to be martial monks (wuseng, 武僧). They are masters of fighting with staves, as well as unarmed combat.

5. Moralistic HeadbandsParallel 5: Both wear a golden headband on their heads, as a symbol of their Buddhist religion.

6. Bin Steel WeaponsParallel 6: Both their primary weapons are made from a divine iron known as bin steel (bintie, 镔铁).

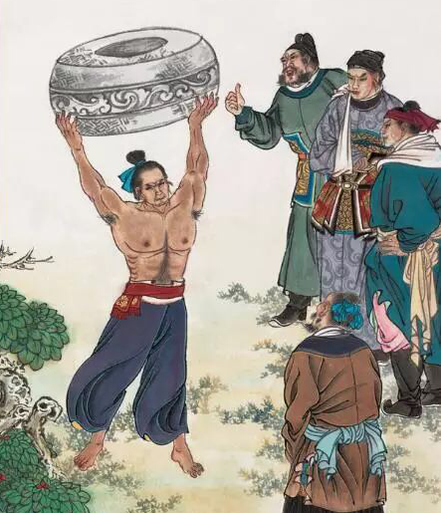

7. Super Strength HeroesParallel 7: Both have displayed their strength by lifting a heavy object that nobody has done before, with both objects’ weights carrying significant figures of 3 and 5.

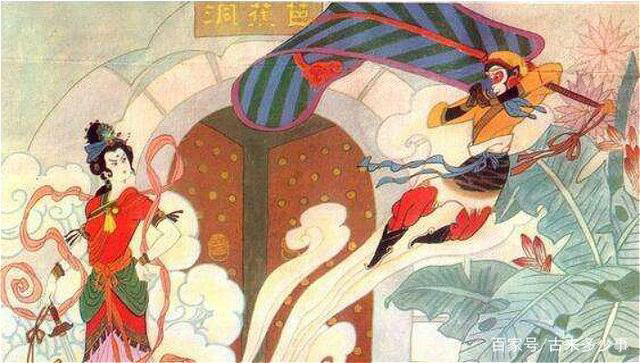

For more information on the origin and meaning behind this point, please see: The Weight of the Monkey King’s Staff: A Literary Origin 8. Meritorious ReformParallel 8: Both were granted amnesty by a particular law order which they achieved great merit in. Wukong: Following being imprisoned for his heavenly crimes, Monkey was aware of his guilt and was ready to reform. On the suggestion of Bodhisattva Guanyin, Wukong agreed to convert to Buddhism and submitted to his new master, Tripitaka, who gave him the religious byname Pilgrim. He rendered a great amount of meritorious service to the law by quelling demons and overcoming ordeals, all to protect the holy Tang Monk on his pilgrimage to the west. After successfully completing his task of escorting Tripitaka to Spirit Mountain, Monkey had reached nirvana and was ultimately appointed by the Tathagata Buddha to become the Buddha Victorious in Battle (douzhan sheng fo, 斗战胜佛) [src. 15-16], a status among the highest in the Buddhist pantheon. [Tathagata said,] “Sun Wukong, when you caused great disturbance at the Celestial Palace, I had to exercise enormous dharma power to have you pressed beneath the Mountain of Five Phases [Five Elements]. Fortunately your Heaven-sent calamity came to an end, and you embraced the Buddhist religion. I am pleased even more by the fact that you were devoted to the scourging of evil and the exaltation of good. Throughout your journey you made great merit by smelting the demons and defeating the fiends. For being faithful in the end as you were in the beginning, I hereby give you the grand promotion and appoint you the Buddha Victorious in Strife [Victorious in Battle]. […]” Wu Song: At one point of the novel, Wu Song joined the heroes of Mount Liang (liangshan, 梁山), a group of outlaws who worked towards standing against the oppression of the corrupt government. When the great news of these heroes reached the emperor’s ears, he agreed to grant the outlaws amnesty, as well as recruiting them to be a sector of the imperial military. Now as a defence force, the heroes were sent on a campaign to fend off foreign invaders, which they all fought courageously. After accomplishing this campaign, the emperor was pleased with their achievements and granted them all noble titles. Wu Song retires and takes up abode at Six-Harmonies [4] Monastery (liuhe si, 六合寺). While there, he was proclaimed the title “Patriarch of Pure Loyalty (qingzhong zushi, 清忠祖师)” by the emperor for his national service [src. 17-18]. Wu Song had rendered merit in opposing the enemy, and was wounded with a lost arm. Now renounced to staying at Six-Harmonies Monastery, he was appointed the Patriarch of Pure Loyalty and was rewarded a hundred thousand guan [5]. There he lived out his days. 9. Forced to become BuddhistsParallel 9: Both only agreed to convert to their Buddhist "Pilgrim" selves as a means of escaping trouble. Wukong: While being imprisoned under Five-Elements Mountain, naturally Monkey would want to be freed. When Bodhisattva Guanyin paid him a visit, Monkey begged the Bodhisattva to have him released from under the mountain. Guanyin explained that some time in the future, a priest from the Tang empire would be able to release him, but the condition is that Monkey must convert to Buddhism and become a disciple for the priest. Desperate to be freed from imprisonment, Monkey agreed without hesitation [src. 19-20]. “Tathāgata deceived me,” said the Great Sage, “and imprisoned me beneath this mountain. For over five hundred years already I have not been able to move. I implore the Bodhisattva to show a little mercy and rescue old Monkey!” “Your sinful karma is very deep,” said the Bodhisattva. “If I rescue you, I fear that you will again perpetrate violence, and that will be bad indeed.” “Now I know the meaning of penitence,” said the Great Sage. “So I entreat the Great Compassion to show me the proper path, for I am willing to practice cultivation.” Wu Song: After killing a trio of men who plotted to murder him, Wu Song became a criminal, wanted by the government for homocide. He sought shelter under a sworn brother, Zhang Qing (张青), and Zhang’s wife, Sun Erniang (孙二娘), who came up with an idea to help Wu find a safe refuge. As mentioned in para. 2.3, 2.5 and 2.6 above, Wu was given a set of Buddhist robes, a precept headband and a pair of precept sabers by Zhang and Sun, to disguise himself in. He accepted these items purely out of his need to evade the attention of government officers and soldiers [src. 21-22]. [Sun Erniang said,] “How can you let brother-in-law go off like this? He's sure to be taken!” 10. Conflict with Sisters-in-LawParallel 10: Both have had to undergo conflict from troubles caused by their sisters-in-law. Wukong: Monkey has one known sister-in-law, named Raksasi (luocha nü, 罗刹女) [7] or more popularly known as Princess Iron-Fan (tieshan gongzhu, 铁扇公主). Monkey’s conflict with her occurred in the episode of the Mountain of Flames (huoyan shan, 火焰山), where he required her Plantain Fan (bajiao shan, 芭蕉扇) to cross the blazing mountain. She did not approve his borrowing request, and Monkey ended up having to heatedly duel his sister-in-law twice and bait her Plantain Fan three times before succeeding [src. 23-24]. All she [Raksasi] could do was to cry out, “Brother-in-law Sun, please spare my life!” Wu Song: In his story, Wu Song has had a total of 3 problematic encounters with two sisters-in-law, one being a fight with the wife of a sworn brother, and the other two from the wife of his biological brother. The greater incident of the latter is much more notable, which I will choose to list singularly in this article. Wu’s sister-in-law Pan Jinlian (潘金莲) is a stunningly beautiful woman, best known to readers as one of the most notorious villainesses in Chinese literature for being an adulterer who murders her husband. Wu Song’s brother and Pan Jinlian’s husband was Wu the Elder (wu dalang, 武大郎), a short, dark, unattractive man who makes a living by selling steamed bread, which to many people, including Jinlian herself, were not satisfied with the two being a couple. One day, Jinlian encounters a nobleman who she is attracted to and has a secret affair with. When her husband Wu the Elder discovers her adulterous acts, he is murdered by Jinlian through poison in his food. The truth about his brother’s death enrages Wu Song, and in strife, Wu disembowels his sister-in-law as a sacrifice to his brother’s spirit [src. 25-26]. He [Wu Song] flashed the knife twice close to Golden Lotus's [Jinlian’s] face. The girl was panic-stricken. ConclusionSeeing that the Water Margin novel predates the official publication of Journey to the West, it is theoretical that Journey to the West author Wu Cheng’en (c. 1500 - 1582, 吴承恩) used the figure of Water Margin’s Wu Song as a basis for his character of the Monkey King. Nonetheless, Pilgrims Sun Wukong and Wu Song are among the greatest literary characters in Chinese culture, and their parallels are apparent, as detailed in this piece. There are still a few more Wukong-Wu Song similarities that are yet to be published, so please keep an eye out for updates on this article. - Notes[1] addressed as “Pilgrim Wu Song”

This is a common trait of the main characters of Water Margin. Every one of the 108 heroes of the novel possesses a nickname, which they are usually addressed by preceding their full name. [2] 13,500 catty (一万三千五百斤) Elvin (2004) notes that one catty (jin, 斤) from the Ming dynasty, when the novel was written, equates to 590 grams. Therefore, 13,500 catties would equal to 7,965 kg or 17,560 lbs. [3] 300-500 catties (三五百斤) In modern measurements, 300-500 catties would equal to 177-295 kg or 390-650 lbs. [4] Six Harmonies (六合) Also translated as: six directions. “Six harmonies” is a literal translation of the original Chinese liuhe (六合), which really refers to the six cardinal directions of gaze. These six directions are: east, west, south, north, up (i.e. Heaven) and down (i.e. Earth). As a phrase, this term can metaphorically refer to the universe or world as an entirety. [5] guan (贯) Also translated as: string of cash. A guan is a measurement of copper coins (i.e. money) in ancient China. One guan equals to 1,000 copper coins, which would normally be tied together by a string through the holes in the centre of the coins. Hence, “string of cash” is the common English translation for guan. Since this translation doesn’t hold the full context of the term, I have kept the original. [6] golden prints (金印) Also translated as: golden seal. In ancient China, a golden seal is a character print tattooed on a convict’s face, as a mark of their criminal status. The character printed is usually the ideogram qiu (囚, lit: prisoner), as an easy sign of identifying criminals if they were ever to escape. [7] Rākṣasī (राक्षसी, 罗刹女) Literal meaning (Sanskirt): female devilish demon. Raksasi or Rakshasi are the female counterparts of Rakshasa, which are cannibalistic demons in Hinduism and Buddhism. In Journey to the West, author Wu Cheng'en is most likely punning with the name as a metaphor for Princess Iron Fan.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sun Wukong and Wu Song: two of the greatest characters in Chinese culture. Explore the parallels they share and see why they are so equally great.

Author

Irwen Wong Inspired by the author of the original article

Jim R. McClanahan |